I'm currently in New Orleans for a meeting this week. After a beautiful Sunday Mass at St. Louis Cathedral presided over by Auxiliary Bishop Shelton Fabre, we decided to visit the New Orleans Museum of Art. It was a wonderful afternoon and they have a decent enough collection there - in particular their impressionist rooms are pretty good.

We were literally out the door when one of the volunteers, named Grace (!), enticed us back in with a promise of free cheese and crackers and free wine. Of course, we went back in. She also mentioned something about two new pieces of art being unveiled for the first time. And, this is where things got interesting.

Fifty years ago, New Orleans was caught up in the turmoil of school integration, at the high point of the civil rights era. There are many images that capture that time.

Some of them are: Rosa Parks refusing to sit at the back of the bus:

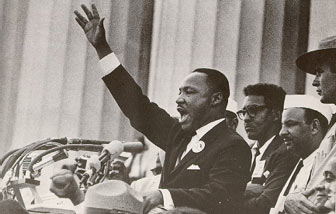

Martin Luther King Jr. marching through the south, or his famous "I Have A Dream" speech on the Washington Mall.

Another of those singular images comes from here in New Orleans. As this city struggled with school integration, one little girl became one of these hallmark images of the change that was so hard-fought for. Her name was Ruby Bridges. As a six year old girl, she was to become the very first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South.

In Spring 1960, Ruby was one of several African-Americans in New Orleans to take a test to determine which children would be the first to attend integrated schools. Six students were chosen, however, two students decided to stay at their old school, and three were transfered. Ruby was the only one assigned to William Frantz. Her father initially was reluctant, but her mother felt strongly that the move was needed not only to give her own daughter a better education, but to "take this step forward ... for all African-American children."

The court-ordered first day of integrated schools in New Orleans was November 14, 1960. As Bridges describes it, "Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras. There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras." Former United States Deputy Marshal Charles Burks later recalled, "She showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She didn't whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we're all very proud of her."

As soon as Bridges got into the school, white parents went in and brought their own children out; all teachers refused to teach while a black child was enrolled. They hired Barbara Henry, from Boston, Massachusetts, to teach Bridges, and for over a year Mrs. Henry taught her alone, "as if she were teaching a whole class." That first day, Bridges and her adult companions spent the entire day in the principal's office; the chaos of the school prevented their moving to the classroom until the second day. Every morning, as Bridges walked to school, one woman would threaten to poison her, because of this, the U.S. Marshals dispatched by President Eisenhower, who were overseeing her safety, only allowed Ruby to eat food that she brought from home. Another woman at the school put a black baby doll in a wooden coffin and protested with it outside the school, a sight that Bridges has said "scared me more than the nasty things people screamed at us." At her mother's suggestion, Bridges began to pray on the way to school, which she found provided protection from the comments yelled at her on the daily walks.

The Bridges family suffered for their decision to send her to William Frantz Elementary: her father lost his job, and her grandparents, who were sharecroppers in Mississippi, were turned off their land. She has noted that many others in the community both black and white showed support in a variety of ways. Some white families continued to send their children to Frantz despite the protests, a neighbor provided her father with a new job, and local people babysat, watched the house as protectors, and walked behind the federal marshals' car on the trips to school.

This first day of school was iconically recalled by Norman Rockwell, in his famous painting, "The Problem We All Live With." It shows this courageous little girl in her bright-white dress and pig tails marching confidently into school escorted by U.S. Marshals.

And, that brings us to today. Armed with our free wine and cheese and crackers we walked into the auditorium of the New Orleans Museum of Art. We sat in the back so we could "leave quickly if this turns out to be boring." On the stage was the original Rockwell (above) with two other paintings covered with sheets on either side.

A woman steps to the podium and after a few opening words says, "Without further ado, I give you, Ruby Bridges." Somehow this casual visit to a minor museum turned out to be an encounter with history. Ruby spoke recalling that dramatic day with palpable detail. She was here because she wanted to commemorate the 50th anniversary of this date in a special way. She had been working with an artist and the two of them collaboratively created two new works of art to help remember that incredible moment. We were enraptured and even had the opportunity to chat with Ruby and with the artist. If it had been a sunny day, our plan was to visit an estuary and Lake Ponchetrain. Instead, we stumbled into history. The new works are below and will hang in the museum here throughout Black History Month.

Artist, subject and painting:

Recalling that day 50 years ago: